Ecological Impacts & Risks Economic Impacts Prevention

Introduction and Spread

In North America, the term “Asian carp” typically refers to two species of invasive fish introduced from Asia: the bighead, or “bigheaded” carp (Hypopthalmichthys nobilis) and the silver carp (Hypopthalmichthys molitrix). These carp are native to China. They were originally imported into the southern United States in the 1970s to provide an inexpensive, fast-growing addition to fresh fish markets. They also served to help keep aquaculture facilities clean. By 1980 the carp were found in natural waters in the Mississippi River Basin. As they have moved north through the Basin they have overwhelmed the Mississippi and Illinois River systems where Asian carp now make up more than 95% of the biomass in some areas. Silver carp can now be found in 12 states. Bighead and silver carp are currently in the Illinois River, which is connected to the Great Lakes via the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal.

.jpg)

Two other species of carp imported to the United States from Asia can also become invasive in the wild, the grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) and the black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus). The herbivorous grass carp, indigenous to eastern Asia where it is cultivated for food, was introduced to the United States to control aquatic weeds in lakes and waterways. The molluscivorous black carp (i.e., feeding on snails, clams, mussels, and other mollusks) is a native of China where it is cultivated for medicinal purposes and as a food source. It was introduced to the United States to provide snail control in aquaculture settings. By the 1990s the grass carp had escaped from cultivation into the wild and can now be found in waters within or adjacent to 45 states where they are considered a threat to natural vegetation. Black carp have also escaped and are now in several locations along the Missouri and Lower Mississippi River Basins.

Ecological Risks and Impacts of Asian Carp

Silver and bighead carp are filter-feeders which feed on plankton (drifting animal, plant, or bacteria organisms that inhabit the open waters of waterbodies), with an apparent preference for bluegreen algae). Asian carp can dominate native fisheries in both abundance and in biomass. Bighead carp can reach 110 pounds, although 30 to 40 pounds is considered average (silver carp are generally smaller). Bighead carp can live over 20 years, maturing at about 7 years. Asian carp can consume 5 to 20 percent of their body weight per day. As most native fish feed on plankton during their larval and juvenile life stages (and some native fish remain planktivorous for life), this high level of feeding on plankton by Asian carp can have serious impacts on the stability of the food web, with bighead carp potentially outcompeting native fish while eliminating the main source of food for larval fish and native planktivorous fish. Native fish considered most at risk include ciscos, bloaters, and yellow perch, which serve as prey to important predatory sportfish including lake trout and walleye.

The Great Lakes provide a wide range of habitat types which would serve as good spawning, recruitment, and maturation areas for Asian carp. Spawning habitat could be provided in the flowing waters of Great Lakes tributaries, while young Asian carp prefer warm, biologically productive, backwaters and wetlands. When not feeding on plankton, Asian carp have been known to feed on detritus and root in the bottom of protected embayments and wetlands. This disturbance could have significant impacts on Great Lakes wetlands and shoreline vegetation which provide spawning habitat for native fish and breeding areas for native waterfowl.

Black carp, being molluscivores, are not a threat to plankton. Should black carp reach the Great Lakes from the Mississippi Basin, however, they could become a threat to native Great Lakes native clam, snail, and mussel populations (particularly those that are rare or endangered), as well as to lake sturgeon (another molluscivore). Black carp can grow to more than 100 pounds and a length of up to seven feet.

In their native habitats, populations of Asian carp are held in check by natural predators. Unfortunately, there are no native Great Lakes fish species large enough to prey on adult Asian carp. White pelicans and eagles have been observed feeding on juvenile Asian carp in the Mississippi Basin. The pelicans, found in the western reaches of the Great Lakes and eagles throughout the Basin may be expected to do the same. Native predatory fish such as largemouth bass may feed on juvenile Asian carp. Given the growth rates of Asian carp, many juveniles can be expected to grow too large too quickly for fish predation to be a significant pressure to hold down carp populations.

Once populations of Asian carp become established with recruitment of young fish exceeding mortality, eradication is considered to be difficult if not impossible. Populations might be minimized in some areas by denying access to spawning tributaries via construction of migration barriers, but this is an expensive proposition which may inadvertently result in negative impacts on native species. The best control of Asian carp is to prevent their introduction into the Great Lakes.

Economic & Recreational Impacts

When frightened by the sound of a boat or personal watercraft motor, silver carp have been known to jump up to ten feet out of the water. The sound of boat motors can cause entire schools of silver carp to jump simultaneously. It is not unusual for 20 to 30 pound silver carp to jump into boats, sometimes resulting in damage to equipment or even injury to occupants. The Great Lakes Commission estimates that almost one million motorboats and personal watercraft are in use the Great Lakes. If the silver carp gets into the lake, around one million recreators could be placed in jeopardy. This could have a negative impact on the $4.5 billion annual Great Lakes commercial and recreational fisheries. Unlike the silver carp, the bighead carp does not jump in response to boat traffic.

if Asian carp feed (and root) extensively in Great Lakes shoreline wetlands, degradation of the water quality and damage to wetland vegetation in native waterfowl breeding areas could threaten the $2.5+ billion annual waterfowl hunting industry.

Prevention

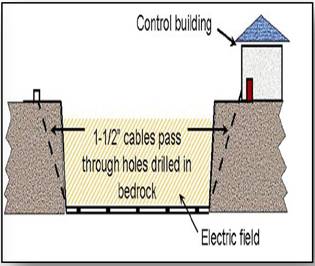

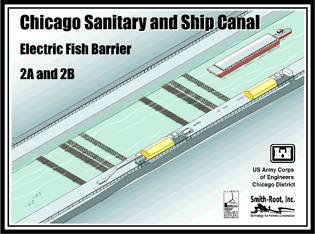

The main pathway through which Asian carp are expected to enter the Great Lakes is the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal (CSSC).

The barriers may prove not to be 100% effective but are currently the main defense against introduction of the carp into the Great Lakes. In 2011, individual carp had been found as close as 22 miles from the barrier. The nearest known breeding population of Asian carp was 50 miles downstream of the barrier; no carp were known to be living above the barrier.

There is also the possibility that Asian carp may get into the Great Lakes through release of live bait into the CSSC above the barrier or directly into the lakes. Live Asian carp being transported to fish markets could also be accidentally or intentionally released into the lakes or their tributaries. The Asian carp has recently been added to the Federal Lacey Act as an injurious species and transport and possession of the fish has been banned.

Additional Asian Carp Information