Feral swine (Sus scrofa), also known as feral pig or wild boar, is a designation that can be applied to the introduced Eurasian boar, escaped or released domestic pig, and crossbreeds of the two. Eurasian boars were introduced to North America as early as 1539 as domestic pigs; additional introductions of other wild Eurasian boar races for hunting occurred through the 1800s and 1900s.

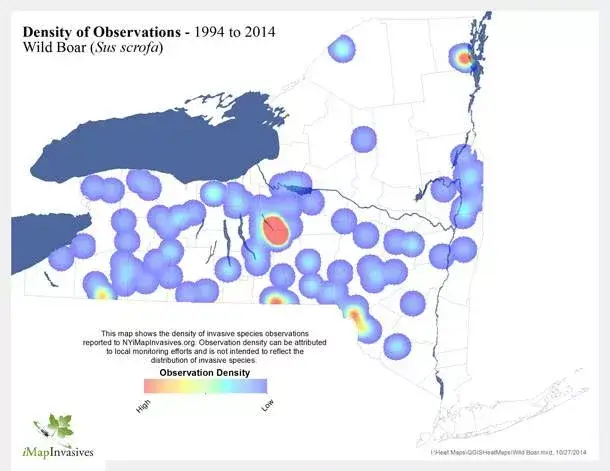

New York populations of feral swine have most likely emerged from escaped and abandoned Eurasian boars kept in captivity and at hunting preserves. Feral swine crossbreed readily with domestic pigs, which has resulted in a wide range of coat colors and body shapes. Many look like typical wild boars, while others may be hard to distinguish from domestic pigs.

Known breeding populations of feral swine in NY (2011) include northwest Cortland, southwest Onondaga, and southern Tioga counties. Pennsylvania also has well established populations in 18 or more counties. Swine may be seen in several Southern Tier border counties with Pennsylvania. Feral hogs have also been observed in a few upstate counties associated with hunting preserves.

Feral pigs can breed at any time with a gestation of 115 days. A female is sexually mature at 1 year of age. Litter sizes range from 1-8 piglets; sows aggressively protect their young. Due to their hardiness and ability to adapt to a wide range of weather conditions and food sources, feral swine can triple their population in a year.

Sows average 110 pounds and boars 130 pounds, but can reach up to 400 pounds. Their appearance can be spotted, belted, or striped, entirely brown, or domestic-looking. Their razor sharp tusks can be 5 inches long before breaking or wearing down. Swine use their tusks to defend themselves and to establish dominance. In New York, the adults have few predators to control herd size.

Feral swine (Sus scrofa) have a list of environmental, agricultural, and human impacts including:

Feral swine are nocturnal; rooting and wallowing in fields and forests, eating crops and hunting. They can decimate acres of fields and gardens every night. Their rooting furrows, 2 to 8” deep, leave a “plowed” look to the landscape.

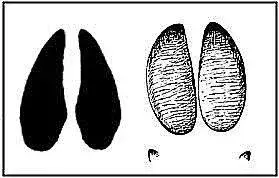

Their tracks and impressions of their coarse hair can be seen at wallowing holes, creeks, and mud holes. After wallowing, which can destroy habitat, they often rub the mud onto nearby trees. Swine tracks are similar to deer tracks, but more rounded. Swine scat can resemble deer, dog, and human scat.

It is illegal in New York to hunt, trap or take any free-ranging Eurasian boar. This law was passed to discourage the illegal release of boars for hunting. Illegal release is the primary way feral swine are expanding across the US. “Free-ranging” is defined as any Eurasian boar that is not lawfully possessed within a completely enclosed or fenced facility from which the animal cannot escape to the wild. (Environmental Conservation Law Section 180.12, Eurasian boar, April 2014).

Feral swine may be excluded from gardens and domestic hog pens with very heavy duty fencing, but since they can burrow, fencing should be monitored. Domestic swine should be securely enclosed.

Shooting can be used to remove one or two feral hogs, but trapping is recommended for removing family groups. Specially-designed corral traps with heavy metal fencing and mechanical doors are needed to capture free-ranging swine.

If you see, shoot, or trap feral swine please report it to your regional NYS DEC Wildlife office http://www.dec.ny.gov/about/50230.html. It is important that natural resource managers know where the swine are.

Feral swine are a threat to New York’s landscape and agriculture. They can cause an immense amount of damage in a short period of time and can transmit disease. Please do not intentionally release swine into the wild for hunting and keep an eye out for escaped domestic pigs. Eradication of feral swine is important.

Curtis, Paul, Associate Professor, Extension Wildlife Specialist, Cornell University. E-mail conversation. August 6, 2011.

Perry, Adam. Wildlife Biologist, New York State Department of Conservation. Phone and e-mail conversation. August 3 and 4, 2011

USDA. 2010. 2010 Status of Feral Swine in New York State. USDA, APHIS-Wildlife Services, Castleton, NY. 19pp.