The Eurasian forb purple loosestrife, Lythrum salicaria, is an erect, branching, perennial that has invaded temperate wetlands throughout North America. It grows in many habitats with wet soils, including marshes, pond and lakesides, along stream and river banks, and in ditches. Purple loosestrife is also capable of establishing in drier soils, and may spread to meadows and even pastured land. It prefers full sun, but can grow in partially shaded environments. Purple loosestrife stem tissue develops air spaces between cells, allowing them to respire when partially submerged in water.

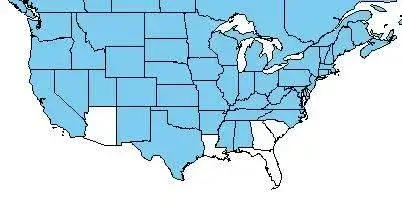

Purple loosestrife is native to Europe, Asia and northern Africa, with a range that extends from Britain to Japan. Purple loosestrife was probably introduced multiple times to North America, both as a contaminant in ship ballast and as an herbal remedy for dysentery, diarrhea, and other digestive ailments. It was well-established in New England by the 1830s, and spread along canals and other waterways. Purportedly sterile cultivars, with many flower colors, are still sold by nurseries. Its range now extends throughout Canada and to all states but Hawaii and Florida.

Purple loosestrife is a perennial, with a dense, woody rootstock that can produce dozens of stems. Shoot emergence and seed germination occurs as early as late April, and flowering begins by mid-June. Seedlings grow rapidly, and first year plants can reach nearly a meter in height and may even produce flowers. The flowers are insect-pollinated, principally by nectar feeders like bees and butterflies. Seed development begins by late July and continues throughout the season and into autumn. A single plant can produce over 2 million seeds. Senescence occurs with the first frost, and dead stems persist throughout the winter.

Though purple loosestrife seeds may not be particularly long-lived in the seed bank (they can survive for at least 3 years), the sheer number of seeds produced allows them to readily capitalize on disturbance. Seeds are dispersed by wind for short distances, by floating, and by anthropogenic means. Germination is best in wet, open soil under relatively warm temperatures (greater than 68°F). The seeds are capable of germinating and establishing under standing water. Though the rootstock buds prolifically, purple loosestrife does not generally spread through vegetative reproduction. Stem fragments can regrow, however, and mowing or otherwise damaging the plants may spread vegetative propagules.

Seedlings have oval cotyledons with long petioles. The stalkless stem leaves are 5-14 cm long, lance-shaped, and opposite. Leaf pairs often grow at 90 degree angles from one another, and leaves near the flowers are sometimes alternate. Stems are upright, angular, and densely hairy. Mature plants can reach up to 4m in height, and older plants often appear bush-like, with sometimes dozens of woody stems growing from a single rootstock. The showy purple flowers have 5-7 petals and grow in pairs or clusters on 10-40 cm tall spikes. Seeds are small (less than 1 mm in length) and lack an endosperm.

Purple loosestrife is competitive and can rapidly displace native species if allowed to establish. Once established, the prolific seed production and dense canopy of purple loosestrife suppresses growth and regeneration of native plant communities. Monotypic stands of purple loosestrife may inhibit nesting by native waterfowl and other birds. Other aquatic wildlife, such as amphibians and turtles, may be similarly affected. The dense roots and stems trap sediments, raising the water table and reducing open waterways, which in turn may diminish the value of managed wetlands and impede water flow.

Small infestations can be pulled by hand, though care must be taken to completely remove the root crown. Glyphosate or triclopyr based herbicides can also effectively control small stands, but as they are expensive and non-selective they are generally unsuitable for large purple loosestrife infestations. Mechanical or chemical management will require multiple years to completely remove adult plants and exhaust the seedbank.

Four species beetles (2 leaf beetles and 2 weevils) have been released in the United States as biocontrol agents for purple loosestrife. They have had some measure of success controlling purple loosestrife populations. The leaf-feeding beetles Galerucella calmariensis and G. pusilla defoliate and attack apical buds as both adults and larvae and can slow growth and diminish seed production. The weevil Nanophyes marmoratus feeds on seeds and flower buds, and the weevil Hylobius transversovittatus attacks both roots (as larvae) and foliage (as adults).

This map shows confirmed observations (green points) submitted to the NYS Invasive Species Database. Absence of data does not necessarily mean absence of the species at that site, but that it has not been reported there. For more information, please visit iMapInvasives.

Butterfield, C., J. Stubbendieck, & J. Stumpf 1996. Species abstracts of highly disruptive exotic plants. Version: 16JUL97. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Home Page, Jamestown, North Dakota.

Gaudet, C.L. & P.A. Keddy 1995. Competitive performance and species distribution in shoreline plant communities: a comparative approach. Ecology 76(1):280 - 291