Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum), also known as Nepalese browntop and Asian stiltgrass, replaces native vegetation in a wide range of ecosystems including forested floodplains, forest edges, stream banks, fields, trails, and ditches. It thrives as a weed in lawns and gardens. Japanese stiltgrass grows well in many light conditions (from deeply shaded hemlock forests to sunny open fields), prefers damp conditions, and often can be found in disturbed areas. It expands into dense stands of grass that prevent desirable vegetation from growing.

Areas infested with Japanese stiltgrass have decreased biodiversity. In addition to the early-season plants that are typically crowded out by invasive species, late-season grasses, sedges, and herbs are also affected. Infested areas also have an increased occurrence of other invasive plants and decreased native wildlife habitat and can provide good habitat for invasive animals including the cotton rat which can further affect local wildlife.

Japanese stiltgrass is not preferred by grazers such as white-tailed deer, goats and horses, which adds to its ability to outcompete native, preferred vegetation. A 2010 study by Pisula and Meiners indicates that Japanese stiltgrass has allelopathic potential to inhibit seed germination.

Japanese stiltgrass is an annual grass that is native to China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, and the Caucasus Mountains. Around 1919, it was found to have been introduced to North America, in Tennessee, most likely through its use as a packing material for porcelain. It is considered invasive in Europe, Africa, Australia, New Zealand, South America, Mexico, and many island nations. Japanese Stiltgrass has extended its range into several Asian countries surrounding its native range, including Turkey, Nepal, and Pakistan.

It could be found in 24 eastern states and territories, from New York to Florida, to Texas, and Puerto Rico (2011). New York State had 16 counties reporting stiltgrass invasions (also in 2011). Japanese stiltgrass is commonly found in association with other invasive plants including garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), Lady’s thumb (Persicaria maculosa), Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), and Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii).

Japanese stiltgrass is able to establish and thrive in a wide range of habitats, and is most often associated with acidic to neutral, moist soils that are high in nitrogen. After disturbance, Japanese stiltgrass readily takes advantage of shaded areas, but can proliferate in sunny openings as well. Causes of disturbance include scouring floods and soil disturbing activity such as the use of heavy equipment (especially logging), tilling, mowing, construction activities, and heavy animal impact, including that from white-tailed deer.

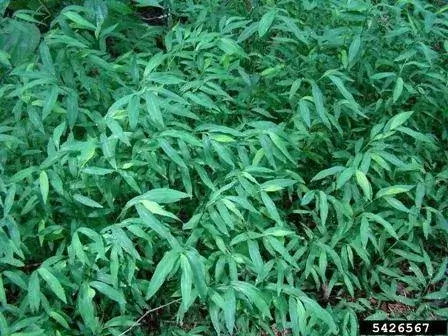

Japanese stiltgrass resembles a small, delicate bamboo and has a sprawling habit. It grows up to 3.5 feet tall. The leaves are 1-3 inches long, asymmetrical with an off-center mid-rib, and are alternately arranged on the stalk. Each lance-shaped leaf has a noticeable stripe of silvery, reflective hairs down the length of the upper leaf surface. Unlike most native grass leaves which are rough in one direction when rubbed, Japanese stiltgrass leaves are smooth in both directions.

In late summer and early fall, one or two delicate flower spikes form at the top of each stem. Each spike of flowers (inflorescence) can either require pollination or be self-fertile depending on soil moisture and sunlight availability. Individual plants can produce between 100 and 1000 seeds. Once those seeds mature the plant dies. Seeds can remain in the soil bank for at least 3 years. Japanese stiltgrass seeds readily germinate after a disturbance.

Japanese stiltgrass spreads over large areas through transportation of those seeds, primarily through the movement of soil, overland water movement, water movement through ditches and streams, and on the feet of animals and humans. Japanese stiltgrass also stolons; rooting at the node joints along the stem, producing new stems. Stolon (or tillering) spread does die off each year, but increases the number of flower spikes on a plant.

Before enacting management practices, be sure to properly identify the grass. There are a few native look-alikes that can be found in association with Japanese stiltgrass (or on their own). Virginia cutgrass (white grass), Leersia virginica, Pennsylvania knotweed, Polygonum persicaria, and some other fine grasses have similar morphology. The unique line of silvery hairs found on the midrib of Japanese stiltgrass is a quick identifier.

Prevention

To minimize the chances of a Japanese stiltgrass infestation, limit disturbing areas and remediate disturbed soils quickly.

Manual/Mechanical Control

Hand pulling of Japanese stiltgrass can be effective for small populations, which is why early detection and rapid response is so important. It is shallow rooted and generally easy to pull. Pull in late summer, ideally before seed set. Pulled plants without seeds can be left on-site; if seeds have formed the plants should be removed. Pulling in late summer allows Japanese stiltgrass seeds in the seed bank to germinate but does not leave enough growing season for them to establish. Do not pull before July as seeds previously left in the seed bank can grow and go to seed.

Populations of Japanese stiltgrass can also be mowed while the plants are in flower but before seed set, late summer to early fall. Mowing will set the plants back, but mowing too early will result in the plants still being able to flower and go to seed.

Soil tilling of infested areas may also be effective. Proceed with the same restrictions as above. Tilling may not be appropriate for all sites.

Due to the length of time seeds are viable in the seed bank sites must be managed and monitored for multiple years. Hand pulling, mowing, and tilling all create disturbances and should be followed with site remediation practices.

Chemical Control

Systemic herbicides can be an interim control of larger Japanese stiltgrass infestations. In the long term, conditions must be altered to prevent reintroduction of Japanese stiltgrass and other invasive plants. Choosing grass specific herbicides over broad-spectrum herbicides can help prevent mortality of non-target plants.

Post-emergent and pre-emergent herbicides have been proven effective. Post-emergent herbicides are applied when the plant is in full leaf and ideally before seed set. Pre-emergent herbicides can be applied at intervals throughout the growing season to prevent germination of Japanese Stiltgrass seeds in the spring as well as when the soil is disturbed so there is potential for additional germination times. Combinations of post and pre-emergent herbicides are viewed as a good tactic, along with continual monitoring for seed germination.

There are reports of Japanese stiltgrass populations becoming resistant to herbicides over time as natural selection allows the more resistant plants to survive and reproduce.

Alternative Methods of Control

The New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation has been battling Japanese stiltgrass for many years in some of its parks and has developed some experimental control techniques. Park biologists have proven that covering stiltgrass with 4-6 inches of mulch (chips, leaf litter) will prevent stiltgrass from emerging (OPRHP Minnewaska State Park Preserve Experiment, 2010, 2011, and Connequot State Park Preserve, 2011). They found that seeding directly into the decomposing layer will reduce future Japanese stitgrass invasions. This treatment is suitable for treating trailside infestations and easily-accessible, small- and mid-sized patches.

Japanese stiltgrass is also not very cold tolerant. Experiments show that using cold temperatures, or dry ice, in late August kills Japanese stiltgrass and may prevent reinvasion for a few years (OPRHP Minnewaska SPP, 2006). Positively, natives are able to recover in the same year as treatment. This experiment has not yet been replicated on a large scale.

Seeding with annual rye can be a temporary restoration practice and is a recommended first stage of complete restoration. Annual rye competes with Japanese stiltgrass enough to allow natives in the seed bank to propagate. Once Japanese stiltgrass has been suppressed for a number of years and natives have a chance to outcompete it, a formal native planting should occur. If applicable to the site, Virginia cutgrass (Leersia virginica ) and jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) are competitive native plants to consider during restoration.

Reviewed by:

Alyssa Reid, Invasive Species Field Supervisor, and Robert T. O’ Brien, Invasive Species Control Field Director, NYS OPRHP – Environmental Management Bureau, Minnewaska State Park Preserve.

This map shows confirmed observations (green points) submitted to the NYS Invasive Species Database. Absence of data does not necessarily mean absence of the species at that site, but that it has not been reported there. For more information, please visit iMapInvasives.

Alyssa Reid, Invasive Species Field Supervisor, NYS OPRHP - Environmental Management Bureau, Minnewaska State Park Preserve. E-mail conversation. January 4, 2012.

Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health

http://www.invasive.org/browse/subinfo.cfm?sub=3051 (8/27/2011)

Fryer, Janet L. 2011. Microstegium vimineum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). [2011, October 17].

National Invasive Species Information Center http://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/plants/stiltgrass.shtml (8/25/2011)

Invasive Plant Atlas: http://www.invasiveplantatlas.org/subject.html?sub=3051 (8/25/2011)

PISULA, N. L. AND S. J. MEINERS. Relative allelopathic potential of invasive plant species in a young disturbed woodland. J. Torrey Bot. Soc. 137: 81–87. 2010

Plant Conservation Alliance’s Alien Plant Working Group Least Wanted Japanese Stiltgrass Fact Sheet. Authors Jil M. Swearingen, National Park Service, Center for Urban Ecology, Washington, DC, Sheherezade Adams, University of Maryland, Frostburg, MD. https://www.invasive.org/alien/fact/mivi1.htm (10/17/2011)

Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas. Swearingen, J., K. Reshetiloff, B. Slattery, and S. Zwicker. 2002. Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas. National Park Service and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, 82 pp

Robert T. O' Brien, Invasive Species Control Field Director, NYS OPRHP - Environmental Management Bureau, Minnewaska State Park Preserve. E-mail conversation. January 4, 2012.