Didymo (Didymosphenia geminata), a globally invasive single-celled algae (diatom), is threatening the streams and rivers of New York State. Didymo secretes massive amounts of branching stalks, creating dense mats that cover the bottoms of streams and rivers. Nicknamed “rock snot” for its gooey appearance, didymo has been confirmed at eight locations in New York State since 2007.

Historically, didymo was considered a widely distributed, yet uncommon, algal species native to the cool, running freshwaters of the northern hemisphere, including northern parts of North America, Europe, and Asia. Records collected over the last 150 years indicate that didymo widely occurred across Europe, including the UK, Norway, and northwest Russia. Didymo diatoms have been reported in the western US for over 100 years, but not as nuisance blooms.

Yet, within the last two decades, didymo blooms have been reported with increasing frequency and intensity across the globe, particularly in locations where historical blooms have not been previously recorded. In North America, didymo blooms were first documented in the 1990s in rivers on Vancouver Island, British Columbia. In the last 20 years, bloom occurrences have spread east across North America and have become increasingly common in the northeastern US, particularly in streams and rivers frequented by anglers and other aquatic recreationists. In 2011, the species could be found in 18 US states and 3 Canadian provinces.

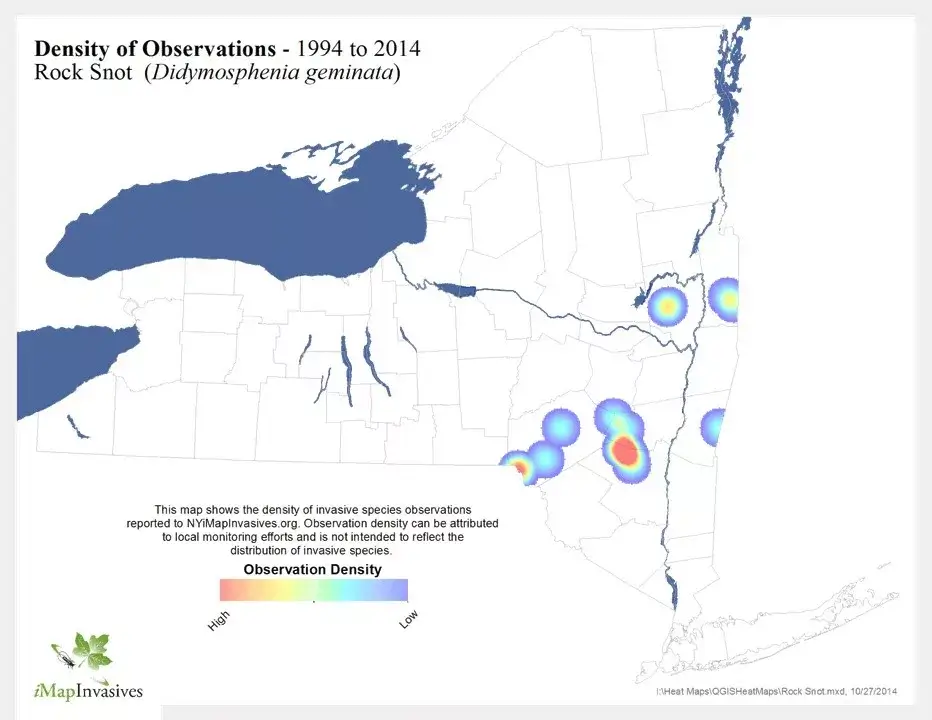

Didymo has been confirmed in eight locations in New York State since 2007, including:

All of these confirmed sites are prime fishing access points where the species has been observed by numerous anglers; it is very possible that Didymo exists in other waterways where it has yet to be identified.

Confirmed Didymo sites in New York State, 2010. Use the navigation tools in the upper left corner of the map to move the map up, down, left or right or to zoom in or out.

Didymo was first detected in the southern hemisphere in New Zealand in 2004, and has continued to spread through numerous watersheds on the South Island (over 32). New Zealand’s didymo blooms have been particularly severe, with mats growing up to 8 inches thick and extending over 2.5 miles in length. Consequently, the government agency Biosecurity New Zealand has been a global leader in efforts to slow the spread and educate the public about didymo.

In 2010, the first didymo blooms in South America were confirmed in several rivers flowing through Patagonia (Chile and Argentina). It was first detected there in the Futaleufú River, a site popular with kayakers from all over the world.

Humans are largely responsible for the recent and prolific spread of didymo beyond its historical range. The microscopic diatoms can cling to fishing gear, waders, boots, and boats, and are capable of surviving at least 40 days outside of a stream as long as they remain in a damp, cool environment.

Felt-soled wading boots are major vectors of didymo as the soles absorb cells like a sponge and provide a temporary habitat for the didymo cells until an angler visits a new site. As a result, natural resource agencies as well as fishing organizations and supply stores like Trout Unlimited and L.L. Bean have promoted non-felt wading boot alternatives. Furthermore, the states of Vermont, Maryland and Alaska have outlawed the use of felt-soled wading boots.

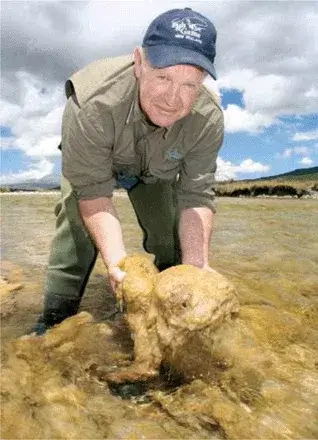

Didymo is a freshwater diatom, a type of single-celled algae that lives attached to rocks and other substrates on the bottom of streams. Under certain conditions, didymo will secrete thick, branching stalks (composed of polysaccharides and protein) outside its cells that form dense tangled mats. The resulting didymo blooms can completely dominate streambeds, capable of lasting several months, with mats greater than 8 in thick and over 0.5 mi long. Unfortunately, the triggers of excessive stalk formation – possibly genetic and/or environmental – are unknown and the subject of current scientific research.

Thick didymo mats resemble fiber-glass insulation or wet toilet paper, inspiring its nickname, “rock snot.” It is generally light tan to brown in color (not green), with stalks sometimes forming long white strands. Clumps of didymo are not slimy, resemble wet wool, and are tough to pull apart.

In contrast to other types of freshwater algae that form nuisance blooms, didymo blooms first appeared in streams with relatively high water quality (clear, cold, low nutrients, stable flow). Often blooms occurred immediately downstream of impoundments, where flows were generally stable, regulated, and nutrient poor. More recently, as its range has expanded, didymo has been recorded in warmer, more nutrient-enriched waters, not associated with dams.

Didymo can alter the diversity and distribution of native stream species and may have negative consequences on how stream ecosystems function.

The extensive stalks produced by didymo cells persist in invaded streams longer than the diatoms themselves and are resistant to degradation; reports from Colorado indicate thick mats of didymo stalks can persist up to 2 months after peak growth. These mats may trap stream sediments, changing the physical nature of the stream bottom and affecting the ability of native stream algae to colonize.

By covering and dominating the substrate, didymo may alter habitat and available food resources for bottom-dwelling stream invertebrates. Recent studies in New Zealand and North America have reported shifts in the invertebrate community as a result of didymo invasion. The proportion of larger sized, environmentally sensitive insect groups like mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies (Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, Trichoptera; known collectively as EPT taxa) tend to decline in didymo infested waters while the proportion of smaller invertebrates, particularly midge larvae (Diptera: Chironomidae), worms (Oligochaeta, Nematoda), and crustaceans (Cladocera), increases. In most cases, the total number of invertebrates actually increases with didymo invasion, possibly as a result of the new habitat or additional food resources provided by the dense didymo stalks.

Shifts in the abundance and diversity of invertebrates as a result of didymo invasion could potentially affect the fish that feed on them. Declines in mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies could threaten trout populations. Furthermore, didymo blooms covering large stretches of the stream bottom could alter stream habitat that is important for fish feeding and spawning. Research on the effects of didymo on native and sport fisheries is still underway. To date, research in North America and New Zealand has been inconclusive, with some studies suggesting no impact of didymo on fish growth and productivity, while others have observed native fish population decline in didymo-invaded waters.

Didymo invasions, although unsightly, do not produce an odor or threaten human health. Infestations do have significant negative impacts on all water-associated recreational activities, particularly sport-fishing. Floating didymo stalks tangle up lines, flies and lures. Additionally, didymo blooms have blocked water intake pipes and canals. Consequently, didymo remains a serious economic concern for fisheries, tourism, irrigation, and hydropower.

Didymo can exist both as a single cell without stalks or as a colony of cells with branching, mat-forming stalks. Unfortunately, invasions are not usually detected until dense didymo mats occur. Researchers who have intensively sampled stream algae by scraping rocks and filtering water from streams with no previous history of didymo blooms have identified single didymo cells when examining those samples under the microscope. Yet, this type of work is extremely time and labor-intensive as didymo cells can be quite rare. Research is now ongoing to develop DNA-based tests for detecting didymo in streams, even at very low concentrations.

Currently, there are no methods available for controlling or eradicating didymo once it has infested a water body. Research in New Zealand is underway to identify and evaluate the safety and effectiveness several didymo-killing chemicals.

Spread prevention is, therefore, the only method we have for protecting our streams and rivers from didymo invasion. Water recreationists must take great care to inspect, clean, and dry all equipment, especially waders and boots when leaving an infested stream or river.

Inspect: Look for and remove all clumps of algae and discard in designated invasive species disposal stations or upland.

Clean: Clean and disinfect any equipment that has come in contact with the water, whether you observe a didymo bloom or not as other aquatic invasive species and diseases may hitchhike on your equipment. Waders and gear should be soaked and/or scrubbed with a 2-percent solution of household bleach or a 5-percent solution of detergent and very hot tap water (> 115°F); ‘eco-friendly’ detergents are not recommended. Absorbent materials (e.g., felt soles, foam) will require prolonged soaking to kill didymo cells (> 30 minutes). Gear could also be placed in a freezer until all of the moisture is frozen solid (note: freezing may damage some gear and will only kill didymo, not necessarily invasive fish diseases).

Dry: Drying will kill didymo, but this method alone is not recommended for absorbent materials because didymo can survive in slightly moist environments for an extended period of time.

If cleaning, fully drying, or freezing is not practical, restrict equipment use to a single water body. One didymo cell transported on gear could result in an invasive didymo bloom – thus, precautionary action is essential!