The hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA, Adelges tsugae) is an aphid-like, invasive insect that poses a serious threat to forest and ornamental hemlock trees (Tsuga spp.) in eastern North America. HWA are most easily recognized by the white “woolly” masses of wax, about half the size of a cotton swab, produced by females in late winter. These fuzzy white masses are readily visible at the base of hemlock needles attached to twigs and persist throughout the year, even long after the adults are dead.

Here’s a handy Hemlock Woolly Adelgid ID video from UMass Amherst:

Hemlock woolly adelgid is native to Japan and possibly China where it is considered a common inhabitant of both forest and ornamental hemlock and spruce trees. It rarely achieves pest outbreak densities or inflicts significant damage to host trees in its native Asian habitat because natural enemies and host plant resistance help keep HWA populations in check.

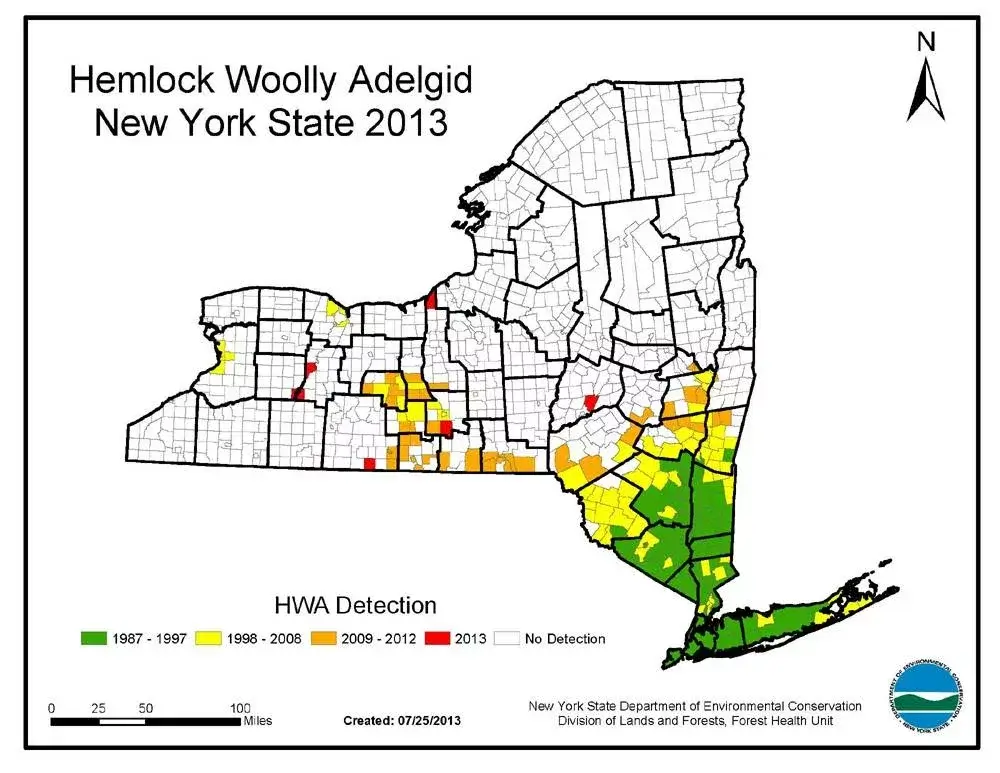

Hemlock woolly adelgid was first detected on the east coast of North America in Richmond, Virginia, in the mid-1950s (Souto et al. 1995). Since its likely accidental introduction from southern Japan (Havill et al. 2006), HWA has spread to 18 eastern states from Georgia to Maine, devastating populations of native eastern (Tsuga canadensis) and Carolina (T. caroliniana) hemlock. HWA now covers nearly half the range of native hemlocks and appears to be spreading about 10 miles a year. It has reached its southern limit, but continues to expand its range to the west and north.

HWA was first detected in New York State in the early 1980s (Souto et al. 1995). Outbreaks have expanded from initial infestations on Long Island and in the Hudson Valley to the Rochester area, the Catskill Mountains, and recently into the Finger Lakes region.

HWA was first detected on the west coast of North America in British Columbia in the 1920s, and now also has a range from northern California to southeastern Alaska. There, it occurs on both mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana) and western hemlock (T. heterophylla) trees. However, HWA does not cause extensive mortality or damage on West Coast hemlocks. Recent comparative genetic analyses suggest that populations in the Pacific Northwest may actually be endemic to that region or originated from very early introductions.

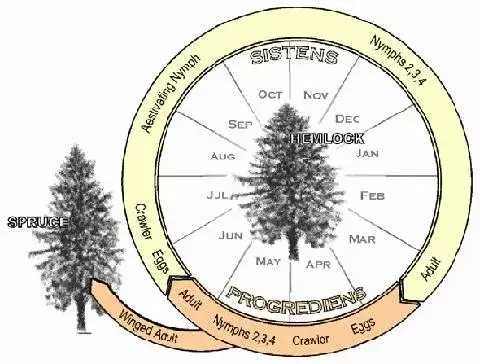

The hemlock woolly adelgid has a complex life cycle, involving two different tree host species as well as asexual and sexual life stages. On eastern hemlock, HWA produces two generations a year, an overwintering generation (sistens) and a spring generation (progrediens); these two generations overlap in the spring. The progrediens has two forms, a wingless form that remains on the hemlock and a winged form (sexuparae) that flies in search of a suitable host spruce tree upon which to start a sexual reproductive cycle (McClure 1995). In New York, there are no suitable spruce, thus the winged HWA are not successful. Each generation has six stages of development: egg, four juvenile (nymph) stages, and the adult.

Overwintering adult females are black, oval, and soft-bodied (approximately 2mm long). They are usually concealed under the white woolly masses of wax (ovisacs) they secrete from special glands on their back-side. From March through May, these females lay 50 to 300 eggs in the woolly masses. The eggs are brownish-orange and very small (0.25mm long by 0.15mm wide). Depending on spring temperatures, eggs hatch from April – June.

Newly hatched nymphs – also known as crawlers – are reddish-brown with a small white fringe near the front (less than 0.5mm long). Crawlers search for suitable sites to settle, usually at the base of the hemlock needles, where they begin to feed and will remain attached to the tree with their specialized sucking mouthparts for the rest of their lives. Crawlers, an important dispersal phase of HWA on hemlocks, can be spread by wind, on the feet of birds, or in the fur of small mammals (McClure 1990). Once settled, these HWA crawlers quickly develop through the four nymph life stages, and mature in June.

Some of the adults of the spring generation (progrediens) are wingless and remain on the hemlock tree, feeding and producing eggs protected by woolly masses just like the overwintering generation, but during June-July. Their offspring hatch into crawlers, quickly settle onto hemlock branches, begin to feed and then enter a dormant period for several months until late October when feeding and development resumes. These nymphs become the next overwintering generation (sistens). The other portion of spring adults has wings and leaves the hemlock trees in June in search of spruce trees to complete the sexual phase of HWA reproduction. However, in North America, no spruce species (Picea spp.) are suitable hosts and any offspring produced die within a few days of feeding. Thus, the winged adult form can be a significant source for HWA population reduction. This is particularly important considering the number of winged adults produced in the spring generation increases with the density of overwintering adelgids, likely a result of changes in nutritional quality in the hemlock host tree.

The hemlock woolly adelgid feeds deep within plant tissues by inserting its long sucking mouthparts (stylets) into the underside of the base of hemlock tree needles. It taps directly into the tree’s food storage cells, not the sap. The tree responds by walling off the wound created by the insertion of the stylets. This disrupts the flow of nutrients to the needles and eventually leads to the death of the needles and twigs. Needles will dry out and lose color, turning gray and eventually dropping from the tree. Terminal buds will also die resulting in little to no new shoot growth. Dieback of major limbs can occur within two years and generally progresses from the bottom of the tree upward (McClure et al 2001).

The hemlock woolly adelgid has an impressive reproductive potential: consider that one female in the winter generation produces an average of 200 eggs which in turn mature and each female of this adult spring generation produces on average another 200 eggs each. That’s 40,000 eggs in one year, starting from one individual female! Thus, HWA populations can grow rapidly in a relatively short period of time. Heavy HWA infestations, particularly in the southern Appalachian Mountains, can kill hemlock trees in as little as four years, with older trees dying more quickly. However, for reasons still under investigation, some infested trees in parts of New England survive for 10 years or more.

Eastern hemlocks play a unique ecological role in eastern forests. Long-lived and shade tolerant, hemlocks may grow in single-species stands or in combination with deciduous hardwood species. They are frequently found growing on exposed slopes as well as protected gorges and stream bottoms. Eastern hemlocks create a cool, damp and shaded microclimate that supports unique terrestrial plant communities, maintains cool stream water temperatures for fish and stream salamanders, and provides important winter habitat structure and food resources for wildlife. Research, particularly in the hard-hit southern hemlock forests, has indicated that declines in hemlock from HWA can result in losses of unique plant and animal assemblages and drastic changes to ecosystem processes (Ellison et al. 2005).

Climate change, particularly warmer summer temperatures, will affect the suitability of habitat for eastern hemlock in the Northeast. Perhaps more troublesome are projected increases in overwintering temperatures that may promote the range expansion of HWA into more northern hemlock forests, areas previously considered unsuitable for HWA survival (Paradis et al. 2008).

Detecting new HWA infestations at the leading edge of its range is critically important for slowing the spread of HWA. Unfortunately, HWA is difficult to detect at low population levels. The first signs of HWA are the presence of the white, woolly ovisacs on the underside of twigs, most often on the newest growth. This white, waxy wool is most easy to observe with the naked eye or through binoculars January through June. Other signs of infestation include graying and dropped needles and limb dieback.

Winter is the optimal time to detect HWA, as the ovisacs are most apparent and the leaves from adjacent deciduous trees that could interfere with observations are absent. An inexperienced observer may confuse several look-alikes with HWA. Spider sacs may look superficially similar but are constructed of much stronger fibers and are usually not closely pressed to hemlock twigs. Spittlebugs, never found in the winter, produce watery, white foam, not wooly and waxy fibers. Scale insects are common, but are found directly on the hemlock needles, not the twigs. Pine pitch and bird droppings may also confuse an untrained observer.

Currently, the two approaches for managing HWA infestations are chemical insecticides and the use of natural enemy predator species as biological control.

Infested hemlock trees can be protected individually with chemical, systemic insecticides. These insecticides, typically applied as a soil drench or an injection into the soil below the organic layer or as a basal bark spray, are incorporated by sap flow into the tree’s tissues and can provide multiple years of protection from a single treatment. However, the costs associated with application, environmental safety concerns about applying insecticides near water resources, and the tremendous reproductive potential of HWA makes this approach less feasible on a broad scale in natural areas. For insecticide guidlines for New York State see Cornell University’s Crop and Pest Management

Guidelines http://ipmguidelines.org/. And, consult a certified pesticide applicator.

Homeowners would be wise to take an integrated management approach for HWA-infested hemlock trees on their property. In lieu of systemic insecticides, spraying hemlock foliage with properly labeled horticultural oils and insecticidal soaps may be effective when trees are small enough to be saturated in order to ensure that the insecticide comes in contact with the adelgid. Owners can reduce hemlock tree stress by watering during drought periods and pruning dead and dying limbs and branches. Avoid the use of nitrogen fertilizers on infested hemlocks as it will actually enhance HWA survival and reproduction. Take care moving plants, logs, and mulch from infested to uninfested areas, particularly when HWA eggs and crawlers are present (March – June). Actions such as moving bird feeders away from hemlocks and removing isolated infested trees from a woodlot may also help prevent further infestations.

Woodlot owners should consult Orwig & Kittredge (2005) for available silvicultural options.

Remember, when using a pesticide, first consult your local CCE office or State pesticide guide to identify insecticides that are registered for use in your state and the proper timing for chemical application.

Ellison, A. M., M. S. Bank, B. D. Clinton, E. A. Colburn, K. Elliott, C. R. Ford, D. R. Foster, B. D. Kloeppel, J. D. Knoepp, G. M. Lovett, J. Mohan, D. A. Orwig, N. L. Rodenhouse, W. V. Sobczak, K. A. Stinson, J. K. Stone, C. M. Swan, J. Thompson, B. V. Holle, and J. R. Webster. 2005. Loss of foundation species: consequences for the structure and dynamics of forested ecosystems. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 3:479-486.

Havill, N. P., M. E. Montgomery, G. Yu, S. Shiyake, and A. Caccone. 2006. Mitochondrial DNA from Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (Hemiptera: Adelgidae) Suggests cryptic speciation and pinpoints the source of the introduction to eastern North America. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 99:195-203.

McClure, M.S. 1990. Role of wind, birds, deer, and humans in the dispersal of hemlock woolly adelgid (Homoptera: Adelgidae). Environmental Entomology, 19(1) 36-43.

McClure, M.S., S.M. Salom, and K.S. Shields. 2001. Hemlock woolly adelgid. FHTET-2001-03. Morgantown, WV: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team; 14 p.

Paradis, A., J. Elkinton, K. Hayhoe, and J. Buonaccorsi. 2008. Role of winter temperature and climate change on the survival and future range expansion of the hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae) in eastern North America. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 13:541-554.

Souto, D., T. Luther, and B. Chianese. 1995. Past and current status of HWA in eastern and Carolina hemlock stands. Pages 9-15 in Proceedings of the First Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Review. USDA Forest Service Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, FHTET 96-10. Charlottesville, VA.

Whitmore, M. 2014 Invasives and Cold Feb 2014. Cornell University, Department of Natural Resources.

Photo and Graphic Credits

Hemlock woolly adelgid infestation - Mark Whitmore, Cornell Cooperative Extension; HWA range map 2008 - US Forest Service, Northern Research Station; HWA range map 2011 - US Forest Service, Northern Research Station; 2012 HWA NYS Range Map- NYS DEC; Hemlock woolly adelgid annual life cycle on hemlock in North America - From Cheah et al. 2004; Adult female HWA with woolly ovisacs and eggs - Michael Montgomery, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org; Adult female HWA, wax removed - Michael Montgomery, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org; HWA nymph in the crawler stage - Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Forestry Archive, Bugwood.org; HWA damage to needles and branches after 2-3 years of infestation - Chris Evans, River to River CWMA, Bugwood.org; HWA infestation resulting in thinning of hemlock crown - Robert L. Anderson, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org; Decline and mortality in infested hemlock in North Carolina - William M. Ciesla, Forest Health Management International, Bugwood.org; Light and heavy infestations of HWA - Mark Whitmore, Cornell Cooperative Extension; HWA look-alikes that may confuse untrained observers - Maine Forest Service, Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Overview; Sasajiscymnus tsugae adult feeding on HWA eggs - US Forest Service, Forest Health Protection—Hemlock Woolly Adelgid - Photo Gallery; Laricobius nigrinus adults feeding on HWA - US Forest Service, Forest Health Protection—Hemlock Woolly Adelgid - Photo Gallery; Scymnus sinuanodulus adults, a biological control agent under consideration, Forest Health Protection—Hemlock Woolly Adelgid - Photo Gallery