If a shoreline property owner in New York or the Northeast complains to you about their water chestnut problem, don’t think they are talking about Chinese takeout. The European water chestnut (Trapa natans), an invasive aquatic plant released inadvertently into waters of the Northeast in the late 1800s, is slowly but inexorably spreading throughout New York State, clogging waterways, lakes and ponds and altering aquatic habitats.

It must be pointed out that this plant species is not the same as the water chestnut which can be purchased in cans at the supermarket. The fruits of T. natans, however, are used as a source of food in Asia and have been utilized for their medicinal (and claimed) magical properties.

T. natans is native to Europe, Asia and Africa. In its native habitat, the plant is kept in check by native insect parasites. These insects are not present in North America and the plant, once released into the wild, is free to reproduce rapidly. T. natans colonizes areas of freshwater lakes and ponds and slow-moving streams and rivers where it forms dense mats of floating vegetation, causing problems for boaters and swimmers and negatively impacting aquatic ecosystem functioning.

Common names: horned water chestnut, water caltrop

T. natans is native to Western Europe and Africa and northeast Asia, including eastern Russia, China, and southeast Asia to Indonesia. T. natans was first introduced to North America in the mid- to late-1870s, when it is known to have been introduced into the Cambridge botanical garden at Harvard University around 1877. It is known to have been planted in other ponds in that area, as well, and also in Concord, MA, in a pond near the Sudbury River. The plant escaped cultivation and was found growing in the Charles River by 1879. The plant was introduced into Collins Lake near Scotia, NY (in the Hudson River-Mohawk River drainage basin) around 1884, possibly as an intentional introduction for waterfowl food or possibly as a water garden escapee.

By the early part of the 1900s, water chestnut was established in the Hudson River. The first Great Lakes Basin introductions were sometime before the late-1950s when the plant was discovered growing in Keuka Lake (one of NY’s Finger Lakes). A major infestation of more than 300 acres exists throughout some 55 miles of Lake Champlain between New York and Vermont. Water chestnut can now be found throughout NY, from the Niagara Frontier through the Finger Lakes, from Lake Champlain to Long Island.

The North American distribution of water chestnut now extends throughout New England, south as far as Virginia, California, and in the Canadian Province of Quebec in a tributary of the Richelieu River. The plant has the potential to spread into the warmer regions of the U.S. as far south as Florida.

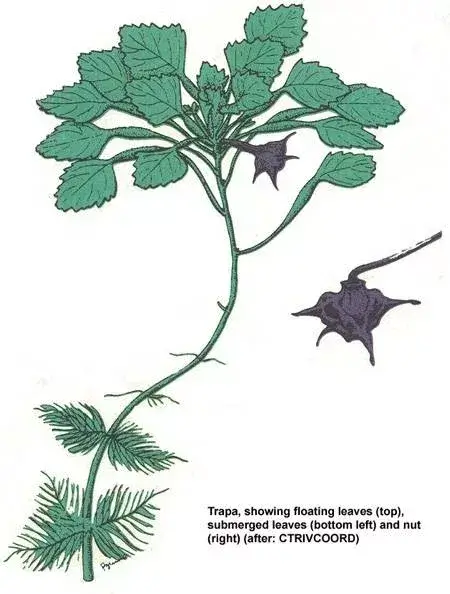

T. natans is a rooted aquatic annual herb that dies back at the end of each growing season. Re-growth is by means of seeds that germinate in the spring. Each seed produces 10 to 15 stems with submerged and floating leaves, terminating in floating rosettes. The feathery submersed leaves can be up to six inches (15 cm) long, and are alternate on the stem forming whorls around the stem. The three-quarter to one and a half inch (2 – 4 cm) glossy green floating leaves are triangular with toothed edges and form rosettes around the end of the stem. The floating leaves also have prominent veins and short, stiff hairs on their lower surface. The petioles (the stalks attaching the leaf blade to the stem; the transition between the stem and the leaf blade) of the floating leaves are two to eight feet (0.6 – 2.4 m) and contain spongy, buoyant bladders, allowing the rosettes to float on the surface of the water. Stems can reach lengths of up to 16 feet (4.9 m), although typical lengths tend to be in the six to eight foot (1.8 – 2.4 m) range. The stems are anchored to the bed of the waterbody by numerous branched roots. Single small, white flowers with four one-third inch (8.3 mm) long petals sprout in the center of the rosette.

Each rosette is capable of producing up to 20 hard, nut-like fruits. Water chestnut starts to produce fruits in July; the fruits, which ripen in about a month, each contain a single seed. The 1 to 1.5 inch (2.5 – 4 cm) wide fruits grow under water and have four very sharp spines. Water chestnut seeds generally fall almost directly beneath their parent plants and serve to propagate the parent colony. Population overwintering is accomplished through mature, greenish brown nuts sinking to the bottom where they can remain viable in the sediment for up to 12 years. Some seeds, however, or plant parts (floating rosettes) that still contain nuts, may be moved downstream in currents. Ducks, geese and other waterfowl may also play a role in the nuts’ dispersal (the spiny nuts have been observed tangled in the feathers of Canada geese). Old nuts, black in color, will float, and are not viable. When deposited in shallow water or on the shore, water chestnut nuts can lead to injuries if stepped on.

Water chestnut has become a significant environmental nuisance throughout much of its range, particularly in the Hudson, Connecticut and Potomac Rivers, and in Lake Champlain. The plant can form nearly impenetrable floating mats of vegetation. These mats create a hazard for boaters and other water recreators. The density of the mats can severely limit light penetration into the water and reduce or eliminate the growth of native aquatic plants beneath the canopy. The reduced plant growth combined with the decomposition of the water chestnut plants which die back each year can result in reduced levels of dissolved oxygen in the water, impact other aquatic organisms, and potentially lead to fish kills. The rapid and abundant growth of water chestnut can also out-compete both submerged and emergent native aquatic vegetation.

Water chestnut has little nutritional or habitat value to fish or waterfowl and can have a significant impact on the use of an infested area by native species.

T. natans likely impacts non-native and invasive plant and animal species in the same manner it impacts natives. Some of the potentially impacted invasive plant species might include: Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum), curly pondweed (Potamogeton crispus), and Eurasian or brittle water-nymph (Najas minor). It is not yet known in a match up of T. natans or and hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata, which invader would outcompete which. Because of its invasiveness and severity of its impacts, T. natans has been listed in federal regulations prohibiting interstate sale/transportation of noxious plants.

Economic impacts result from T. natan’s impenetrable mats of vegetation which can impede swimming, boating, commercial navigation, fishing, and waterfowl hunting. Untreated populations of such an aquatic invasive species also can result in losses to shoreline property values and, as a result, to local government property tax revenues. As mentioned earlier, the sharp, spiny nuts can result in puncture injuries to swimmers and recreators walking along the shore of infested areas and can injure the feet of livestock and horses, as well.

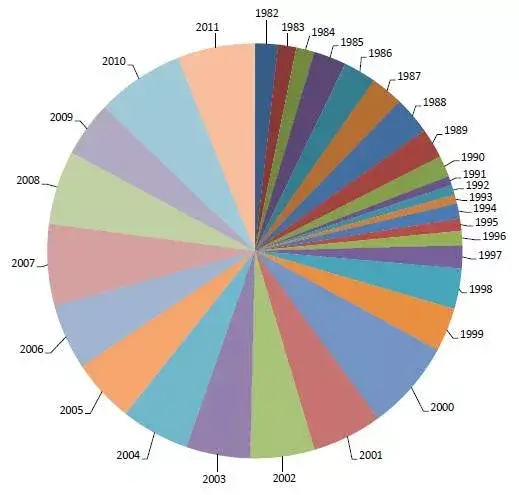

One example of the cost of managing T. natans in a waterbody is the experience of the States of New York and Vermont on Lake Champlain. From 1982 through 2011, $9,600,000 has been spent on Trapa control in the lake with funding from a number of sources including: the two states; the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; the U.S. Department of Agriculture; Ducks Unlimited; the Lake Champlain Basin Program; and The Nature Conservancy. A combination of hand pulling and mechanical harvesting has been used on the lake since the early-1980s. Significant reductions of T. natans populations resulted from this prolonged annual control effort, however, every time that funds were reduced, rapid grow back of the species and extension of its range in the lake was observed.

It is much easier and less expensive to control newly introduced populations of T. natans. Early detection of introductions and a rapid control response are key to preventing high-impact infestations. Because T. natans is an annual plant, effective control can be achieved if seed formation is prevented. Small populations can be controlled by hand pulling working from canoes or kayaks.

Large infestations usually require the use of mechanical harvesters or the application of aquatic herbicides. Regardless of treatment type, it should ideally take place before the fruit has ripened and dropped to the bottom forming a long-term seed bank. Because of the potential of unintentional spread of floating plant parts offsite, mechanical harvesting should be undertaken only by trained and certified equipment operators. Since water chestnut overwinters entirely by seeds that may remain viable in the sediment for up to 12 years, repeated annual control is critical to deplete the seed bank. Treatment generally is needed for five to twelve years to ensure complete eradication and can be very expensive (see Economic Impact, above).

Potential negative impacts to non-target species and public perceptions regarding the use of chemicals in recreational waters have limited chemical control of T. natans except as a treatment of last resort and usually only in still or sluggishly flowing waters. The herbicide 2,4-D has been tested and shown to be non-adverse on non-target species. 2,4-D has been used widely in the U.S. Another herbicide that is effective on T. natans is glyphosate. Application of aquatic herbicides requires both a licensed pesticide applicator and a permit from your state environmental regulatory agency.

The unfortunate fact is that for large infestations of water chestnut (i.e. those too large to be controlled by hand-pulling) over the long-term mechanical and chemical control measures have proven to be impractical to provide an economically sustainable control of water chestnut. Scientists have now turned to the potential of biocontrol agents to serve as a long-term solution to water chestnut infestations.

A number of potential biological control agents were found in field surveys in the native European and Asian ranges of water chestnut. The most promising biocontrol species appeared to be the leaf beetle Galerucella birmanica. Unfortunately, field observations in China suggested that G. birmanica may also attack native water shield (Brasenia schreberi) in addition to Trapa natans. This host non-specificity could be problematic to the use of the beetle for biocontrol in North America.

Laboratory and field tests initially indicated that out of 19 different plant species in 13 different families, G. birmanica laid eggs and completed development only on species of Trapa and B. schreberi. Adult G. birmanica in the field and lab indicated that the beetles showed a strong preference for T. natans. This preference continued even after the water chestnut was completely defoliated; adults resisted migrating to nearby water shield. While this is very promising news, additional studies on host specificity with additional North American aquatic plants are on-going. [Ding, et. al., 2006]

Blossey B, Schroeder D, Hight S, Malecki R. 1994. Host specificity and environmental impact of two leaf beetles (Galerucella calmariensis and G. pusilla) for biological control of water chestnut (Trapa natans). Weed Science 42:134-140.

Deck J, Nosko P. 2002. Population establishment, dispersal, and impact of Galerucella pusilla and G. calmariensis, introduced to control water chestnut in central Ontario. Biological Control 23: 228-236.

Ding J, Blossey B, Du Y, Zheng F. 2006. Galerucella birmanica (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a promising potential biological control agent of water chestnut, Trapa natans. Biological Control. Vol.36, Issue 1, Pages 80–90

Fernald ML. 1950. Gray’s Manual of Botany. 8th ed. American Book Company, N.Y.

Gleason HA. 1957. The New Britton and Brown Illustrated Flora of the Northeastern U.S. and Adjacent Canada. New York Botanical Gardens, N.Y.

Methe BA, Soracco RJ, Madsen JD, Boylen CW. 1993. Seed production and growth of water chestnut as influenced by cutting. J. Aquat. Plant Manage. 31: 154-157.

Mills EL, Leach JH, Carlton JT, Secor CL. 1993. Exotic species in the Great Lakes: A history of biotic crises and anthropogenic introductions. Journal of Great Lakes Research 19: 1-54.

Mullin BH. 1998. The biology and management of water chestnut (Trapa natans L.). Weed Technology 12:397-401.

Pemberton RW. 2002. Water Chestnut. In: Van Driesche R., et al. 2002. Biological Control of Invasive Plants in the Eastern United States. USDA Forest Service Publication FHTET-2002-04.

Rawinski T. 1982. The ecology and management of water chestnut (Trapa natans L.) in central New York. M.S. thesis, Cornell University.

Vermont Invasive Exotic Plant Fact Sheet Series: Water Chestnut. Vermont Agency of Natural Resources and The Nature Conservancy, Vermont Chapter. June, 1998.

Hunt T, Marangelo P. 2012. 2011 Water Chestnut Management Program: Lake Champlain and Inland Vermont Waters, Final Report. Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation. May 2012.